Trio Elégiaque No. 2 in D minor

- classical music

- Oct 13, 2023

- 4 min read

Trio élégiaque No. 2, Op. 9 in D minor

Composer: Sergei Rachmaninoff

Date of publication: December 15, 1893

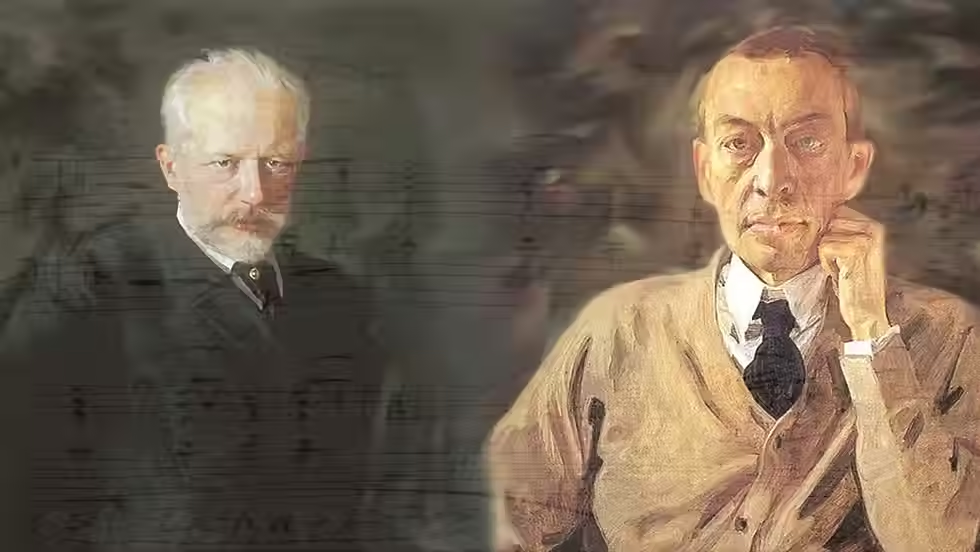

Rachmaninoff always had an intimate connection with Tchaikovsky. As a child, Rachmaninoff was introduced to and fell in love with Tchaikovsky’s works through his older sister’s performances. In 1885, Rachmaninoff began studying under Nikolay Zverev, who enthusiastically exposed his students to music; his students lived in his house, he brought them to performances in Moscow theaters, and every Sunday evening, he would invite special guests to talk about music. One of these guests happened to be Tchaikovsky. Upon entering the Moscow Conservatory in the same year, Rachmaninoff met Tchaikovsky again, who immediately took interest in Rachmaninoff after grading one of his theory exams. Tchaikovsky was so impressed with the young pianist’s work that he added tens of little “plus” signs to Rachmaninoff’s score and demanded to see all of Rachmaninoff’s works for criticism. Tchaikovsky would then recommend Rachmaninoff to study counterpoint with Sergey Taneyev and in 1888 proclaimed that he “predicted a great future [for Rachmaninoff]”.

Over the years, their admiration for each other blossomed. Tchaikovsky’s patronage was a huge motivator for Rachmaninoff. He paid great attention to his theory classes. He published numerous works, including his first piano concerto, his Morceaux de Fantasie, Op. 3, and his symphonic poems, Aleko and The Rock. In 1892 he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the highest honors, the Great Gold Medal. Due to these successes, Tchaikovsky practically championed Rachmaninoff as his successor. In 1891, Tchaikovsky trusted Rachmaninoff with making a better transcription for his ballet The Sleeping Beauty for piano than even Rachmaninoff’s teacher’s! Tchaikovsky attended many of Rachmaninoff’s performances, heartily praising them in letters to his friends. He often accompanied performances of his own works with those of Rachmaninoff’s. In an interview in 1892, Tchaikovsky admitted that once his musical inspiration faded, he would “make way for younger people… [including] Arensky, Davydov, and Rachmaninoff, who has created a wonderful opera setting of Pushkin's poem The Gypsies.” To which Rachmaninoff happily commented, “That made me so glad! My hearty thanks to the old man for not having forgotten about me.”

Tchaikovsky was, in a sense, a father-figure to Rachmaninoff; a guide and source of inspiration. Lyricism, melodies, heavy emotion, tension, and color in Rachmaninoff’s works are “Tchaikovsky-esque,” especially in his earlier works. Rachmaninoff later reflected on his relationship with his mentor: “Of all the people and artists whom I have had occasion to meet, Tchaikovsky was the most enchanting. His delicacy of spirit was unique. He was modest like all truly great men and simple as only very few are.” Rachmaninoff was understandably devastated by Tchaikovsky’s death on November 6, 1893. Revering the great Russian composer, Rachmaninoff forced himself to compose a tribute on the same day.

On December 15, 1893, Rachmaninoff finished his tribute, titled Trio élégiaque No. 2. The piece is characteristically Rachmaninoff but also Tchaikovsky. Rachmaninoff borrowed several motivic and thematic features from Tchaikovsky’s own Trio in A minor, fittingly composed to commemorate the life of the late Nikolai Rubinstein in 1882. Both pieces share a similar first movement: heavy, plodding chords played by the piano accompanied by a passioned, lamenting violin and a cello assisting the other voices. Rachmaninoff’s second movement takes on the form of a theme and variation, similar to the Tchaikovsky’s 12 variation Trio with a grand sense of conviction. Both of their final movements also begin with a sense of triumph that dies down as the piece ends. In Rachmaninoff’s case, the first movement’s somber motif returns, full with emotion, and is brought to a grieving conclusion, reminiscent of Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony.

It is somewhat strange that Rachmaninoff chose to write a trio dedicated to Tchaikovsky. Tchaikovsky only ever wrote one trio for violin, cello, and piano. Rachmaninoff is also clearly less comfortable writing for strings. He had only written a quartet and another trio before 1893 and he had not even finished his quartet. His Trio élégiaque No. 2 is practically a piano showcase; the cello mainly reinforces the pianist’s left hand or the violin’s melodies in octaves and the violin serves to add complexity and a contrasting voice to the piano (or just to make the pianist’s life easier by not needing to worry about playing another entire voice alongside an already difficult backbone). Perhaps Rachmaninoff wanted to pay homage to Tchaikovsky’s breathtaking orchestral and symphonic works by incorporating stringed instruments. Regardless, it is clear Rachmaninoff was deeply moved by his mentor’s death. The piece itself is 50 minutes long, but more importantly, Rachmaninoff hit a block. Until the 20th century, Rachmaninoff barely composed any other works, fell into a depression, and was forced to take teach piano, which he hated. However, after his resurgence in the 1900s, Rachmaninoff once again ascended to popularity through works including his concertos, sonatas, preludes, and composer-themed variations. Through his works in a grand, uniquely Rachmaninoff style, Rachmaninoff lived up to the expectations of succeeding the great composers of the past. Tchaikovsky’s death, in a morbid sense, was a turning point for Rachmaninoff – an exit from youth and the beginning of his mature years as a performer and composer.

Movements:

I. Moderato

II. Quasi Varizione

III. Allegro risoluto

Fun Fact:

Some think Rachmaninoff’s first Trio élégiaque foreshadowed Tchaikovsky’s death, since it was composed just the year before and thematically like his second Trio élégiaque. However, this may be a mere coincidence, since Tchaikovsky was healthy at the time.